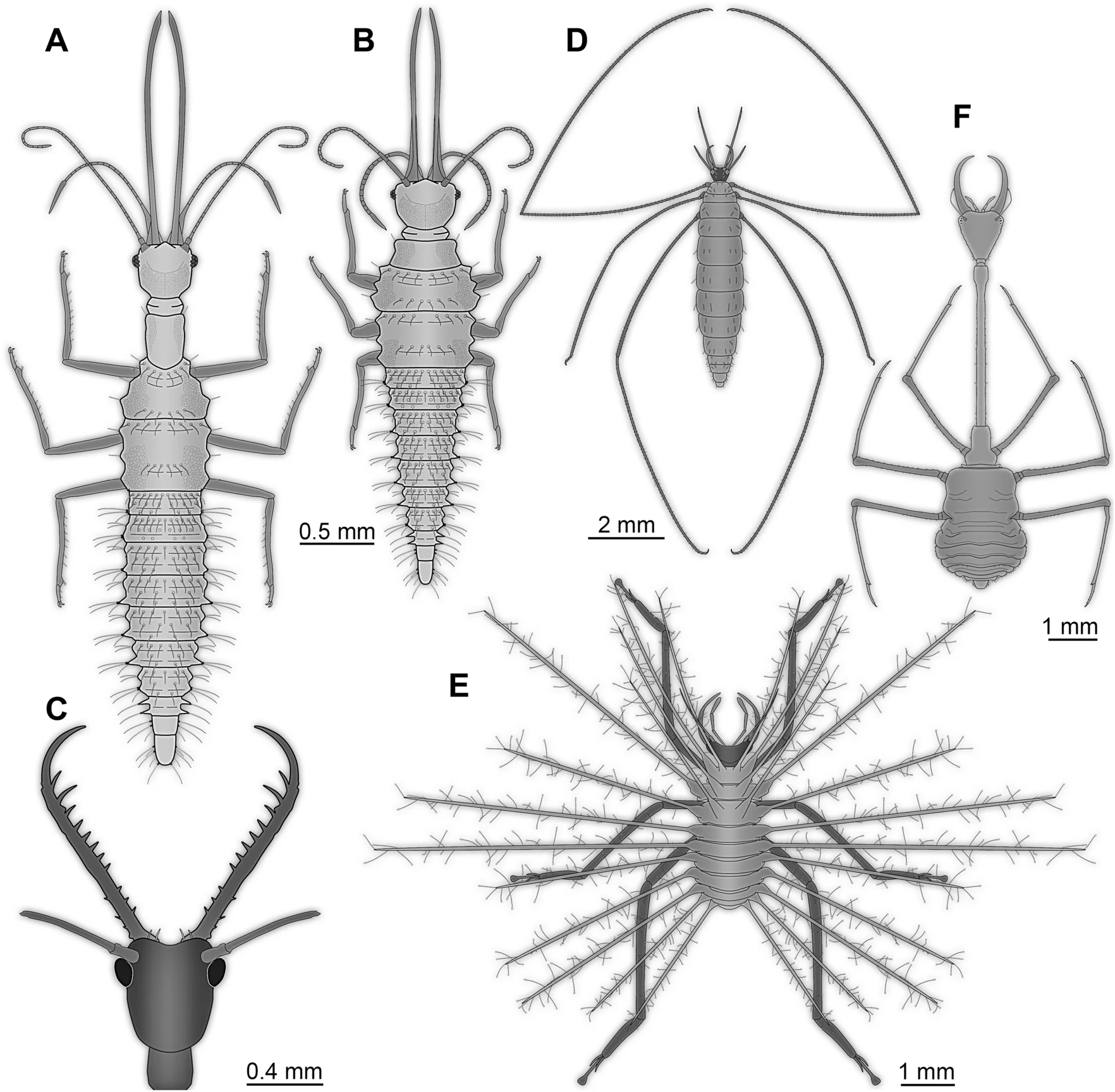

Lacewing larvae of the “Supersting”-type in amber from Myanmar; all with elongate appendages. (A, B) Specimen BUB 3133, (A) Overview in ventral view. (B) Close-up of tip of hind leg; arrows mark tarsal claws. (C, D) Specimen PED 0316. (C) Overview in dorsal view. (D) Close-up of broke-off tips of preserved stylets. (E) Specimen BUB 3348a. at antennule, hc head capsule, lp labial palp, sy stylet. Credit: DOI: 10.1038/s41598-021-99480-w

Among the finds are fossil lacewing larvae whose morphology differs strikingly from that of the 'typical' insect larva. Their most unusual features are their elongated appendages—particularly the mouthparts called stylets, which look like hypodermic needles. "As in the case of all modern species of lacewings, these larvae were probably predators, but we know nothing about their prey," says Haug. Modern species feed on aphids, immobilizing them by injecting them with venom, and then feeding on their contents. However, the cuticle of aphids is so soft that much smaller sucking appendages would be sufficient to penetrate them. "The long stylet may have acted as a means of keeping their wounded victims at a distance until the toxin began to take effect," Haug suggests. However, since the most extreme examples of elongated appendages are found in species that are now extinct, he and his colleagues believe that this body organization may have proven to be an evolutionary dead end.

The fossil larvae shed light on ecology and developmental biology

Given that lacewings are now comparatively rare, the degree of species richness of the lacewing group found among the amber-encased fossils from Myanmar suggests that the group was more diverse in the Cretaceous Period. This in turn implies that these insects played a much more prominent ecological role at that time. "They were probably an important constituent of the food chain, since they effectively transformed practically inedible materials into nutritious food for birds," says Haug.

The fossils also shed light on another aspect of insect evolution. Up to now, it has been assumed that the relative lengths of structures such as antennae, sensory organs and legs are subject to developmental constraints. In most insect larvae, these body parts are usually significantly shorter than they are in the mature adult and—generally speaking—the larva is more worm-like in form. However, in many of the lacewing larvae found in amber, antennae, mouthparts and legs tend to be markedly elongated. "This demonstrates that, from the point of view of developmental biology, there are no strictly defined limits to the lengths of such structures," Haug points out.

The nature of the habitat

However, one other aspect of insect evolution continues to puzzle developmental biologists. Did the first insects that were capable of flight spend their larval lives on land or in the water? Joachim Haug and his team found a clue to the solution in 99-million-year-old amber from Myanmar—a specimen of the fossil dragonfly species Arcanodraco filicauda. They interpret the morphology of this find as indicating that the earliest flying insects spent the initial stages of their life cycle in water. Other evidence supports this notion. Dragonflies, mayflies and stoneflies represent very old lineages of flying insects—and their modern descendants spend the larval phase (which can last for several years) in water, before they undergo metamorphosis and take to the air as—short-lived—adults. "It looks as if the earliest flying insects were highly dependent on an aquatic environment for reproduction," says Haug. Perhaps the first successful take-off from the surface of a pond was accomplished with the aid of wings that acted as sails.

Source: https://phys.org/news/2021-10-intriguing-insect-fossils-amber.html

Fucking beautiful.

Further lacewing larvae with extreme morphologies. (A–E) Larvae from Myanmar amber. (A, B) “Supersting”-type. (A) Based on specimen BUB 3133 (see Fig. 1A). (B) Original “Supersting” larva11. (C) Head of “Superfang” larva12. (D) Larva of Pedanoptera arachnophila (simplified from26). (E) Larva of Hallucinochrysa diogenesi (simplified from36,37). (F) Extant larva of Necrophylus27.